More than a year ago, I wrote a collection of heuristics and mental models I rely on when making important decisions. Since then I’ve continued to ponder the complex psychology of trading, and why most people fail at this beguiling dance with fortune. I converged on a central theme that underlie these mental models. This theme elucidates a fundamental principle, which I believe is integral to achieving financial outperformance.

Before proceeding further, I want to emphasize that these are simply reflections of my thoughts from navigating through multiple market cycles. You may find this helpful now, or in the future — if so I am glad it has helped. It is certainly not meant to be a magic bullet for financial success.

Towards Trust-Minimization in Cyberspace

Consider the following truisms:

- In cyberspace, everyone has a voice regardless of merit or status

- The effort required to counter disinformation is an order of magnitude greater than the effort to produce it

- The consequences of disseminating disinformation are often insubstantial

From the above, we can logically conclude that the majority of non-objective information on the Internet is unlikely to be useful, and consequentially it is impossible to censor or curb disinformation effectively at scale. This is starkly illustrated by the Whac-A-Mole game being played by social media platforms against the legions of internet bots and trolls. As one mole is knocked down, countless others pop up, rendering the platforms’ responses perpetually ineffective and delayed.

The issue is expected to worsen progressively with the advent of deep fakes and AI-generated content — it is estimated that up to 90% of content will be synthetically generated by 2026. This report by Europol goes on to say that “the increase in synthetic media and improved technology has given rise to disinformation possibilities.” Also consider the fact that false information spreads much faster than the truth and it is a recipe for disaster.

This explains why online disinformation campaigns are often so successful and more cost-efficient than traditional ones. They are becoming an increasingly favored technique for nation states. Future warfare will no longer be defined by juggernauts of steel and gunpowder; rather, the battlefield will lie in the ethereal battlegrounds of cyberspace.

This also plays out on a smaller scale. Many corporations and individuals today are willing to produce content at any cost for engagement. The incentives are severely misaligned — most content is designed for maximum engagement, but disguised as if intended for your well-being. Because of the many innate cognitive biases that work against us, we often treat subjective opinions of others as objective truths of our own.

The dangers are further compounded by the increasing popularity of short-form content because it conditions people to disregard the often lengthy critical-thinking processes required to reach a rational conclusion. Clichés peddled by influencers — like “what goes up must come down”, “no pain no gain” and “be greedy when others are fearful” — are far likelier to influence the decision of an average trader than rigorous analysis.

If we do not guard our minds carefully, we will suffer greatly from the deleterious effects of disinformation. This quote from Epictetus has always been very illuminating for me:

“If a person gave away your body to some passerby, you’d be furious. Yet you hand over your mind to anyone who comes along, so they may abuse you, leaving it disturbed and troubled—have you no shame in that?” —EPICTETUS, ENCHIRIDION, 28

In my experience, the most effective way to deal with this is to treat all non-objective information as false by default. I have a mental pool of information I have confirmed to be true that forms the basis of any decision-making. Before any new information can be added to this pool, it must be rigorously scrutinized and verified by me or someone I trust, else completely discarded. This has to be a conscious and deliberate effort, as any information you come across, when neither disproven nor verified, can subconsciously influence decision-making in the direction of your bias.

However, this behavior often leads to accusations of being a skeptic or a pessimist, and invites platitudes like “optimists always win”. To that, I will say two things:

There is a fine line between optimism and delusion, and most people begin their journey in the markets as optimists. More pertinently, I don’t view this as skepticism. Skeptics are commonly portrayed as miserable pessimists — people that are quick to reject non-conforming ideas. Whereas in this mode of thinking, one is indifferent towards the acceptance or rejection of an idea. How an idea is formed is more important than the idea itself.

A hyperconnected world necessitates such cautious thinking, which naturally manifests itself as a form of contrarianism. People who have deep conviction about unpopular or unconventional investment ideas are people who I find to be the most impressive. It takes confidence and skill to be able to diverge from the herd. If your investment ideas are entirely inspired by what is currently trending, then that’s a bad sign.

The Confidence to not Conform

Reflecting on my own experiences, most of my best trades have stemmed from ideas that are infrequently talked about, or initially held in very low regard by the public.

Throughout much of my academic journey, I often avoided attending anything that required attentive listening, much to the chagrin of my lecturers and peers. Reading was a more efficient medium for knowledge transfer than listening for me, and I did not want to limit my productivity because of social norms. This practice cumulatively saved me thousands of hours that I instead used to learn various skills — skills that have played a big factor in my career.

If what you are doing is similar to what everyone else is doing, especially in the context of financial markets, you are likely to achieve an average outcome. If you want to achieve extreme success, then you have to be willing to deviate from society’s ideals and expectations of you.

Throughout history, there have been plenty of examples of how heterodoxical or contrarian thinking have led to great success — not just in the financial realm, but also in important scientific disciplines.

Copernicus’s theory of heliocentrism, often thought of as the spark of the Scientific Revolution, was almost never published. He only relented after the strong urging of his friend, in 1543 — he died that very same year. He had conceived of the idea 29 years ago, but chose not to reveal it to anyone except a few close friends out of fear of persecution. His theory wildly contradicted the geocentric model, a view heavily endorsed by the church at that time. If Copernicus had died a year earlier, would his theory never have been published?

Heinsenberg upended the world of Newtonian physics when he proposed a fundamental new way to view particles — a theory now known as the Uncertainty Principle. It was a stark departure from the status quo, which viewed the universe as completely deterministic, leading Einstein to proclaim his famous quote, “God does not play dice with the universe”. Today, that theory is central to the field of quantum mechanics.

Society has generally sided with the status quo irrespective of its merits, and punishes people for having strong ideas that do not conform with the consensus view. Even today, this manifests itself in many negative-sum societal behavior. Cancel-culture serves to punish those who dare speak up. Virtue signaling continues to reinforce herd behavior and foster echo bubbles.

Consider what Joseph Lehman, the author who coined the term Overton Window, said:

Lawmakers are actually in the business of detecting where the window is, and then moving to be in accordance with it.

The entire premise as a contrarian is to position yourself to profit from this process of change. To bring it back into investing:

Buy on heresy, sell on orthodoxy

The contrarian thinker often thinks about what could happen in the future instead of being absorbed in the present. As the masses are busy obsessing over the latest investment fad, the intelligent contrarian places bets on sound, but obscure ideas that has yet to enter mainstream conversation. Because the contrarian is by definition the small minority, their actions will unlikely move price very much. As some of these ideas get accepted by authorities and thought leaders, they slowly become dogma. The masses then flock quickly to this new idea, not because they suddenly think the idea is great — it has likely been around for a long time — but because of their fear of missing out. Fear is a huge accelerant to herd mentality, and when you don’t have complete information about something, it is often easier to rely on someone else who you believe knows more than you. The blind leads the blind. These are exactly the situations that the contrarian investor profits heavily from.

Therefore, it is often the contrarian thinker who leads, and the masses who follow. One of my favorite quotes is from George Bernard Shaw, which says:

The reasonable man adapts himself to the world; the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore, all progress depends on the unreasonable man.

The Phantasm of the Tails

The Gaussian distribution underpins a lot of the financial models that we use today to calculate and manage risk (modern portfolio theory, VAR, credit risk models, …) which are further entrenched in government regulations. While this assumption is necessary to simplify a lot of very complex processes — models are after all, always a simplification of reality — it insufficiently accounts for fat tails, or “black swans” as popularized by Taleb. History is littered with the corpses of investors who relied too heavily on the Gaussian distribution.

Being an effective contrarian means carefully considering situations others would consider inconceivable, and then later shaping it within the constraints of practicality to form a sensible strategy. Learning and modelling from the past is important, but one should never confuse the meaning of unprecedented with impossible.

It is also unwise to predict black swans in an attempt to explicitly profit from them. Even if you were sure one was inevitable, timing it would still be impossible. Instead, you should build your portfolio so that it is sufficiently robust to them, a strategy referred to as long-tail hedging. If you are hedged, you will be in a great position to take advantage of these extreme situations. Paradoxically, it has been my experience that hedging costs are the cheapest at exactly the moments when they are the most prudent to put on.

Reactive Contrarianism

Being a contrarian is often a prerequisite, not a panacea for successful trading. Impulsively going against consensus out of spite can yield disastrous results.

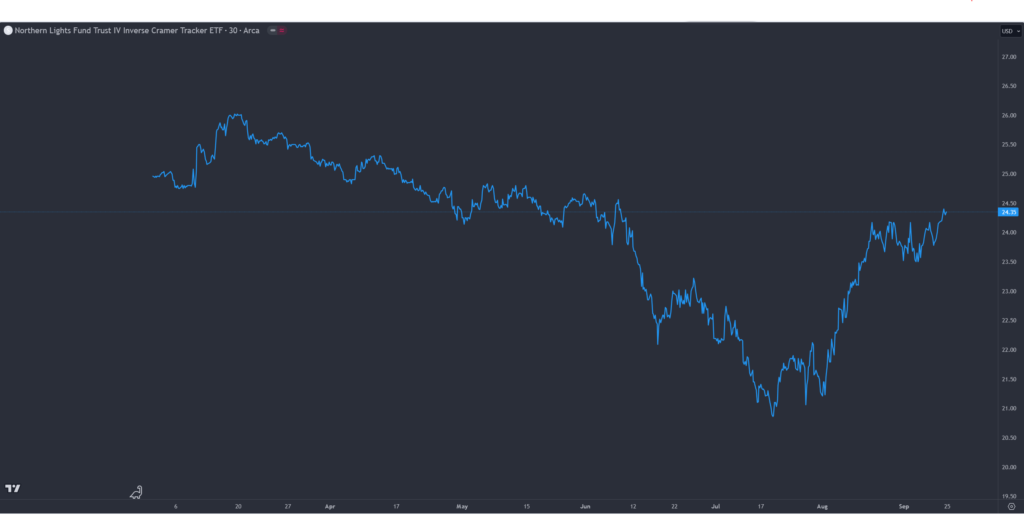

There are many anecdotes of how some (dis)influencers embody the perfect counter-trading signal — when they buy, you sell. While they may be wrong more often than not, trying to profit from them consistently is difficult, because market timing and other external factors can work against you in the short-term. Furthermore, if they are consistently wrong, then that in itself constitutes an exploitable signal!

Price performance of the Inverse Cramer ETF

Consensus Trades

When an investment strategy becomes overwhelmingly consensus, then it is likely that those ideas have already been priced in by markets. Efficient Market Hypothesis works terrifyingly well on ideas that everyone has converged on. If you know that a positive or negative event might or will occur, it does not mean you can reliably profit off of it, because if you know, then unless you are an insider, so does everybody else. You either be the first to act on the information, or act slowly by carefully considering the following:

- How early am I to receive this information in comparison to other people?

- If I do not think I am early, then under what circumstances is this not priced in?

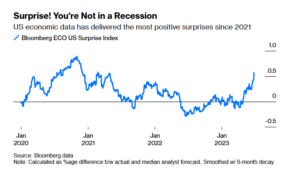

As 2022 was ending, the inevitability of impending recession dominated media headlines.

Economists Place 70% Chance for US Recession in 2023

Stock Market’s Brutal Year Leaves Wall Street With Little Faith in a Rebound

Forecast for US Recession Within Year Hits 100% in Blow to Biden

Now:

Goldman Cuts US Recession Chances to 15% on Improved Inflation

Powell Says Fed’s Staff Is No Longer Forecasting a Recession

When I think that an idea has become consensus but I find myself agreeable to it, I spend a greater deal of effort than I normally would scrutinizing it.

The Battle Against Attrition

On top of societal pressure, there is also a great battle to be fought against oneself. Even the best investors have capitulated high-conviction positions due to mental attrition.

Stanley Druckenmiller infamously shorted $200M worth of tech stocks during the Dot-com bubble. In just 3 weeks, he was forced to cover the position near the top for a $600M loss. Remarkably, every company he shorted eventually went bankrupt. When asked about the trade, his response was illuminating:

You asked me what I learned. I didn’t learn anything. I already knew that I wasn’t supposed to do that. I was just an emotional basketcase and I couldn’t help myself. So maybe I learned not to do it again, but I already knew that.”

To be a truly effective contrarian, you must possess the privilege and mental strength to be wrong for a long time. Ask yourself — are you in a position to do this? The fund manager who has placed a highly asymmetric bet a few years early will likely be relinquished of his position long before his idea plays out. When everyone else is getting rich from dog coins and cash-grab NFTs, it takes a lot of discipline to remain prudent with risk management.

The only solution to this is to make your approach as path-independent as possible, especially removing elements of market-timing. For example, instead of shorting an overextended rally, simply invest in liquid, low-risk assets like Treasuries. If your theory proves to be correct, you will make more by being well-capitalized during the correction than you would have made shorting.

Concluding Remarks

Effective contrarians often have a deep understanding of the fundamentals and exhibit sophisticated thought processes. The bad ones will always be quick to refute, speak in absolutes and portray a defeatist attitude.

I believe the coming decade will greatly reward those who practice this philosophy. Fiscal imprudence by governments, monetary adventurism by central bankers, and conflict between two hegemons in an increasingly multi-polar world all casts a great pall on the post-WW2 international order and financial stability we have all so taken for granted. We are starting to live in a world where the black swans of yesterday are the headlines of tomorrow. We need look no further than in our own industry to see this. In such a world, let this philosophy be our bulwark against the dark horses of markets.